A defining feature of the Roman occupation of Britain was the changing nature of food. In the Silchester Gallery at Reading Museum you can see examples of how people living in Roman Britain cooked, ate, and took care of their homes.

In this blog post, Tamisan Latherow, fourth-year PhD candidate at the University of Reading, shares her research into the state of food production, cooking and agriculture in Roman Britain. Discover how and what people ate, why Julius Caesar thought Britons kept chickens as pets, and how to cook snails the Roman way.

In 55 BC, Julius Caesar crossed the Channel and spent two summers attempting to quell the Celts. While Roman influence would start to alter the local way of living, it wasn't until the 43 AD second invasion under Emperor Claudius that Britannia, as it came to be known, would forever be changed. [1]

A defining feature of Roman occupation was the changing structure of food. Iron Age Celtic Britons were known for a combination of pastoral (animal and animal products) and arable farming (crops). Several varieties of wheat, including Emmer, Einkhorn, Rivet, and Spelt were grown; Emmer and Spelt being the two most important for bread and trade. Oats, rye, barley, and millet were also produced, mostly for animal feed or lower grade bread or porridge. Flax for linen and oil, beans, peas, wild herbs (ramps and garlic) and fat hen (a type of primitive parsnip) would have been available and cultivated as well. [2]

From the animal side, cattle, goats, and sheep were kept for their meat, milk, hides, and wool; and pigs for ham, sausages, and bacon. Blood, collected from living animals (the wounds would be cauterized to keep the animal alive after collection), would be mixed into breads, porridges, and sausages, creating a more nutritious 'black' bread or pudding. [3]

According to Caesar, chickens, geese, and hares were bred and kept, but not eaten.

"They do not regard it lawful to eat the hare, and the cock, and the goose; they, however, breed them for amusement and pleasure."

Julius Caesar - Gallic War Book V, Ch. 12.

According to historians, the miscommunication seems to come from the Celtic practice of separating out the cocks, which were used for fighting, and geese, which were used as guards, their loud cries warning of visitors and animals. [4]

Celts living close to rivers or the coast ate fish, with baking and broiling being the most popular methods of cooking. Posidonius noted that baked fish was often cooked with salt, vinegar, and cumin, and that meals would have consisted of several small loaves of bread, and meat broiled or roasted on a spit or over charcoal. [5]

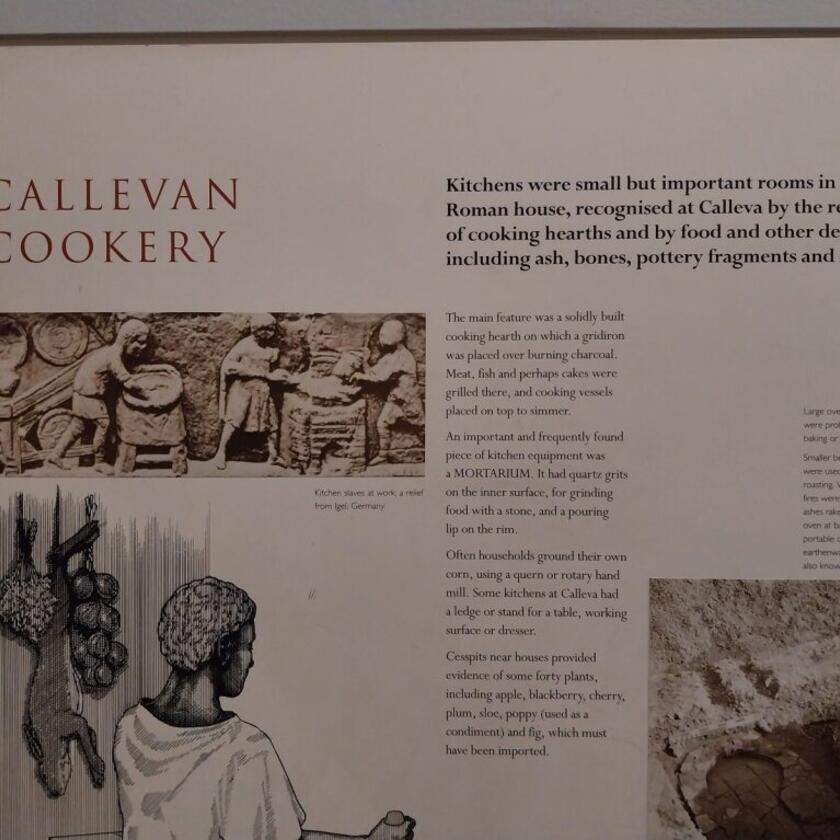

The influx of Roman soldiers, tradesmen, and families from all over the Roman Empire over the next 400 years of occupation led to vast changes in local diets and cultivation. Many of the foods and cooking techniques we use today derive from Roman practices. Iron pans called paterae found on Hadrian's Wall, for example, were brought by soldiers from Campania, Italy and frying pans called sartago that resemble modern camping cook pans with foldable handles were used to cook meat and fish. [6]

Chicken was a popular dish for Romans, which might explain why Caesar was so confused. There are fifteen recorded recipes made with sweet and sour sauces found in the quintessential Roman cookbook, Apicius. While the lower classes and slaves would have dined on coarse bread, gruel, bean or pea pottages, and perhaps a little meat, the upper classes would have had a more varied diet. Pates, minced meat, and omelet-style dishes were popular in the Apicius recipes, as were sweet and salty combinations, such as fish sauce with melon. [6, 7]

Some of the more unusual foods would have been snails and dormice, which would have been imported to Britain in the early 3rd century, along with recipes for the most important of Roman ingredients: garum, a fermented fish sauce. A modern equivalent (for those not wishing to wait 2-3 months for fish to rot in a barrel of salt in the sun) would be any of the Asian fish sauces. [8]

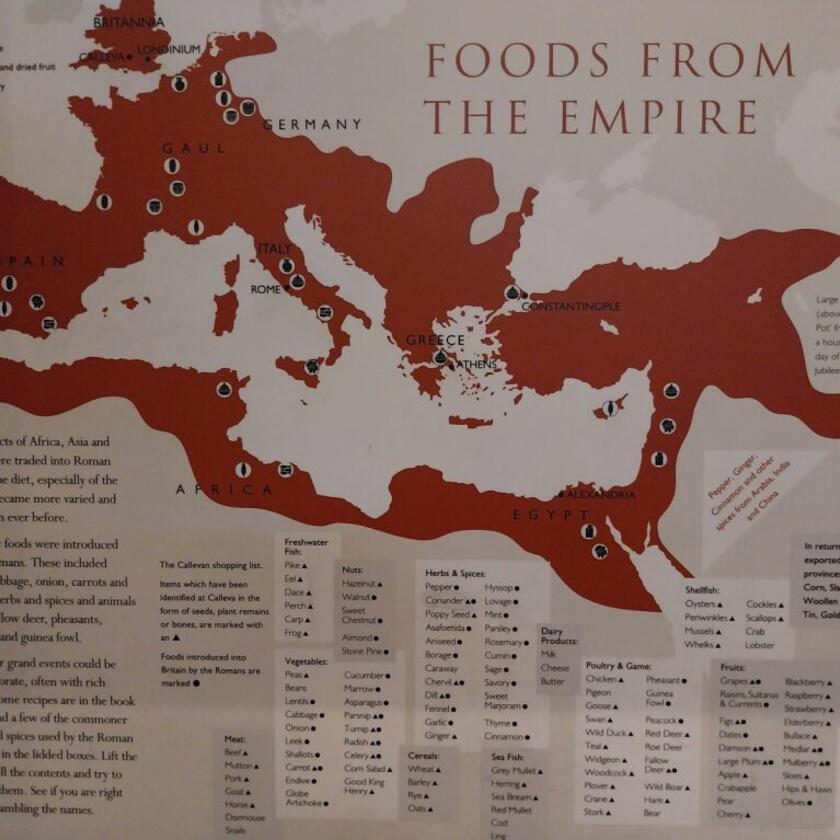

Archaeological evidence from Roman Britain villas shows that fruit and vegetable gardens were an important part of upper-class rural or peri-urban landscapes. Cabbages, carrots, celery, onions, leeks, shallots, endives, cucumbers, marrows, asparagus, turnips, artichokes, and parsnips were all grown in vegetable gardens, while figs, grapes, apples, pears, cherries, plums, damsons, mulberries, dates, and olives were cultivated in orchards, along trellised walls, and in containers in the warmest parts of the villas. Likewise, lentils, pine nuts, almonds, walnuts and sesames, and herbs such as coriander, dill, and fennel were also introduced. In all, over 50 different varieties of some of our 'typical' foods were brought by the Romans. [9]

Much of the information regarding food comes from cookbooks such as Apicius, frescoes found in the villas themselves, or archaeological evidence found in storage bins, fire and garbage pits (not to mention the toilets). As we attempted to reproduce a simple meal of snails, artichokes, grilled fish, bread, and 'cheese' cake, we found that much of the flavouring came from sauces.

Land snails, the most common being 'Roman' snails, would have been raised in small pens in the garden and fed on grass and greens, then with milk and grain to fatten them up before eating. Unfortunately, the only snails I was able to procure were Cerithidea obtusa, a type of sea snail called a mud creeper. While the Roman snail is much easier to cook and remove from the shell, this version requires a lot of sucking to dislodge the meat.

Boiled artichokes were also served, along with boiled eggs and grilled sea bass and tuna. The snails, artichokes, and fish all had their own sauces, while the ricotta-based cakes were soaked in honey and sprinkled with a bit of mace. Figs or dates would have typically been served with this dessert. Panis Quadratus, an extremely dense sourdough bread with Italian herbs and olives was also served.

Food is one of the greatest teachers of history. It gives insights into culture, trade, politics, religion, and class, and opens dialogues between people. By attempting historical recipes, we can explore just what type of influence history has on the present and future.

Take a walk through your town and see what plants are growing. That apple tree in the centre of the street may have been ‘planted’ by Roman soldiers as they marched along on campaign. The core tossed out without thought to grow in an old cattle pasture. Or the blood sausage in your Sunday Roast may have been created by Iron Age farmers in order to eke out a little more nutrition during the cold winter months.

Every meal has a story to tell. This is just one of them. If you were to look at your pantry today, what would your food tell future people about your life?

Garum Recipe:

3.5 kg small fish (anchovies and/or sardines rinsed and de-scaled, but intact)

1 kg salt (you want 20-25% salt water brine, strong enough for a raw egg to float when added)

Method

Arrange the anchovies and sardines in a vase, alternating layers of salt and layers of fish, covering all with salt. After 3-4 days, stir well the contents of the vase. Repeat 3-4 times per day for two or three months.

When the fish is well liquefied, strain the liquid part with a sift and separate it from the solid residual. Keep the liquamen (strained liquid) and allec (residual solids) in the fridge and use them within a couple of months.

Roman Sea Bass Recipe: [11]

-

sea bass

-

30 ml white wine vinegar

-

100 ml dry white wine

-

honey

-

extra virgin olive oil

-

wheat starch

-

garum

-

dry onion

-

black pepper

-

lovage

-

parsley

-

oregano

Method

Grind the spices with dry onion. Choose the quantity freely according to your taste: early cooking sources, like this one, do not usually specify the amount of ingredients. Then mince the parsley and oregano. We suggest using more parsley than oregano to prevent the latter from becoming overpowering. Remember that Apicius' recipes always aim for a balance between flavors.

To make the sauce, pour extra virgin olive oil, wine, vinegar, and garum into a saucepan, with a bit of honey to balance the acidity. Use just a little garum: it's very salty. Let the sauce boil, then add the spices and onion with the diluted starch. When the sauce thickens, add the fresh herbs and take off the heat.

Poach the sea bass. Apicius gives no direction about how to do this step. We chose to follow the instructions of later cookbooks and used water, vinegar, and salt.

Now, plate the sea bass, pouring over the sauce with minced parsley and oregano.

Roman Snails Recipe: [12]

1-2 Dozen snails (live or canned)

60ml olive oil

3g asafoetida (or equal parts garlic and onion powder mixed)

9g garum (or fish sauce)

6g ground long pepper (or regular black pepper)

Method

In a small bowl, mix olive oil, asafoetida, garum, and pepper. Set aside.

Over medium heat, add oil to a frying pan, add snails and cook for 2 minutes. Add sauce and cook 4-5 minutes. Remove from heat, serve with left over sauce from pan.

Libum - Roman Cheese Cake Recipe: [14]

Plain Libum

900g cow or goat's milk ricotta

450g whole wheat flour

2 eggs

Bay leaves

Sweetened Libum

900g cow or goat's milk ricotta

500g whole wheat flour

2 eggs

Bay leaves

235ml honey, pomegranate, grape, or date syrup

Ground mace

Method

Preheat oven 180C.

Mix flour, cheese, and eggs together to form dough. Knead for a few minutes, then rest for 1 minute uncovered.

Cut in half and roll into round boules.

Line a baking sheet with parchment. Place bay leaves on paper to cover bottom of each boule.

Bake, uncovered, 1 hour. Place in bowl of honey to soak until cool. Serve with a sprinkle of mace.

Footnotes

[1] Roman Britain. (n.d.) Roman Britain - An Introduction. https://www.roman-britain.co.uk/

[2] Enayat, M. (2014). Celtic and Roman food and feasting practices: A multiproxy study across Europe and Britain.

[3] Considine, H. (2017) Ancient Artisans - Iron Age Food. https://youtu.be/DZLf1r28cBs

[4] Roman Britain. (n.d.) Farming in Celtic Britain. https://www.roman-britain.co.uk/the-celts-and-celtic-life/farming-in-ce…;

[5] Alcock Joan P. (2010) Food in Roman Britain. The History Press.

[6] Hobbs, R. and Jackson, R. (2010) Roman Britain. The British Museum Press.

[7] Apicius (1958) The Roman Cookery Book: A Critical Translation of the Art of Cooking for Use in the Study and the Kitchen. Trans. Flower, B. and Rosenbaum, E. London: Harrap.

[8] Greene, M. (2004) Herefordshire Through Time - Food and Diet in Roman Britain. https://htt.herefordshire.gov.uk/herefordshires-past/the-romano-british…;

[9] Historical Italian Cooking (n.d.) How to Make Garum. https://historicalitaliancooking.home.blog/english/recipes/how-to-make-…

[10] Johnson, M. (2021) Panis Quadratus: Ancient Bread of Pompeii. https://breadtopia.com/panis-quadratus-ancient-bread-of-pompeii/

[11] Historical Italian Cooking (n.d.) Ancient Roman Sea Bass. https://historicalitaliancooking.home.blog/english/recipes/ancient-roma…;

[12] Miller, M. (2021) Tasting History - Ancient Roman Fast Food Restaurants. https://youtu.be/qtmOdxEVytA

[13] Miller, M. (2022) Tasting History - Growing an Ancient Roman Garden. https://youtu.be/IVpiIa_Txws

[14] Monaco, F. (2017) Libum or Cato's Honey Cake. https://tavolamediterranea.com/2017/08/16/libum-catos-cake-bread/